For all real numbers $ x $, the condition $ |3x - 20| + |3x - 40| = 20 $ necessarily holds if

For all real numbers $ x $, the condition $ |3x - 20| + |3x - 40| = 20 $ necessarily holds if

\(6 < x < 11\)

\(7 < x < 12\)

\(10 < x < 15\)

\(9 < x < 14\)

The Correct Option is B

Approach Solution - 1

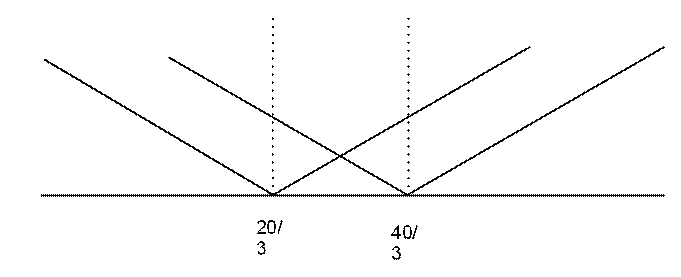

The minimum value of the modulus function is zero, which means the minimum value for each of the two modulus functions occurs at \(x =\frac{ 20}{3}\) and \(x = \frac{40}{3}\), respectively.

Consider the expression:

\[ |3x - 20| + |3x - 40| = 20 \]

Behavior of the Function:

- For values of \( x < \frac{20}{3} \), both expressions inside the modulus decrease, so their sum increases.

- For values of \( x > \frac{40}{3} \), both expressions increase together, so again, the sum increases.

- In the range \( \left[ \frac{20}{3}, \frac{40}{3} \right] \), one function increases while the other decreases, exactly balancing each other.

This means:

\[ \text{The sum stays constant at 20 when } x \in \left[ \frac{20}{3}, \frac{40}{3} \right] \Rightarrow x \in [6.66, 13.33] \]

Correct Option:

Among the given choices, the interval that lies completely within this range is:

\( \boxed{(B)\ 7 < x < 12} \)

Approach Solution -2

Solving the Equation:

\[ |3x - 20| + |3x - 40| = 20 \]

Case 1: \( x \geq \frac{40}{3} \)

In this case, both expressions inside the absolute values are non-negative:

\[ |3x - 20| = 3x - 20, \quad |3x - 40| = 3x - 40 \]

\[ \Rightarrow (3x - 20) + (3x - 40) = 20 \\ \Rightarrow 6x - 60 = 20 \\ \Rightarrow 6x = 80 \\ \Rightarrow x = \frac{80}{6} = \frac{40}{3} \approx 13.33 \]

Case 2: \( \frac{20}{3} \leq x < \frac{40}{3} \)

Here, \(3x - 20\) is positive and \(3x - 40\) is negative:

\[ |3x - 20| = 3x - 20, \quad |3x - 40| = -(3x - 40) = 40 - 3x \]

\[ \Rightarrow (3x - 20) + (40 - 3x) = 20 \\ \Rightarrow 20 = 20 \quad \text{(Always true)} \]

So, the equation holds for all \( x \in \left[ \frac{20}{3}, \frac{40}{3} \right] \)

Case 3: \( x < \frac{20}{3} \)

In this case, both expressions are negative:

\[ |3x - 20| = 20 - 3x, \quad |3x - 40| = 40 - 3x \]

\[ \Rightarrow (20 - 3x) + (40 - 3x) = 20 \\ \Rightarrow 60 - 6x = 20 \\ \Rightarrow 6x = 40 \\ \Rightarrow x = \frac{20}{3} \]

This value is not valid in this case since it contradicts the condition \( x < \frac{20}{3} \). So, no solution in this case.

Conclusion:

Valid values of \( x \) lie in:

\[ \frac{20}{3} \leq x \leq \frac{40}{3} \Rightarrow 6.67 \leq x \leq 13.33 \]

From the given options, the interval (B) \( 7 < x < 12 \) lies completely within the valid solution range.

Final Answer:

Option (B): \( \boxed{7 < x < 12} \)

Top Questions on Linear Inequalities

- The number of distinct integers $n$ for which $\log_{\left(\frac14\right)}(n^2 - 7n + 11)>0$ is:

- CAT - 2025

- Quantitative Aptitude

- Linear Inequalities

For any natural number $k$, let $a_k = 3^k$. The smallest natural number $m$ for which \[ (a_1)^1 \times (a_2)^2 \times \dots \times (a_{20})^{20} \;<\; a_{21} \times a_{22} \times \dots \times a_{20+m} \] is:

- CAT - 2025

- Quantitative Aptitude

- Linear Inequalities

- Match List I with List II

LIST I LIST II A. The solution set of the inequality \(-5x > 3, x\in R\), is I. \([\frac{20}{7},∞)\) B. The solution set of the inequality is, \(\frac{-7x}{4} ≤ -5, x\in R\) is, II. \([\frac{4}{7},∞)\) C. The solution set of the inequality \(7x-4≥0, x\in R\) is, III. \((-∞,\frac{7}{5})\) D. The solution set of the inequality \(9x-4 < 4x+3, x\in R\) is, IV. \((-∞,-\frac{3}{5})\) Choose the correct answer from the options given below:- CUET (UG) - 2023

- Mathematics

- Linear Inequalities

- If \(c=\frac{16x}{y}+\frac{49y}{x} \)for some non-zero real numbers x and y,then c cannot take the value

- CAT - 2022

- Quantitative Aptitude

- Linear Inequalities

- The largest real value of a for which the equation\( |x+a|+|x−1|=2\) has an infinite number of solutions for x is

- CAT - 2022

- Quantitative Aptitude

- Linear Inequalities

Questions Asked in CAT exam

- The passage given below is followed by four summaries. Choose the option that best captures the essence of the passage.

In the dynamic realm of creativity, artists often find themselves at the crossroads between drawing inspiration from diverse cultures and inadvertently crossing into the territory of cultural appropriation. Inspiration is the lifeblood of creativity, driving artists to create works that resonate across borders. In a globalized era of the modern world, artists draw from a vast array of cultural influences. When approached respectfully, inspiration becomes a bridge, fostering understanding and appreciation of cultural diversity. However, the line between inspiration and cultural appropriation can be thin and easily blurred.

Cultural appropriation occurs when elements from a particular culture are borrowed without proper understanding, respect, or acknowledgment. This leads to the commodification of sacred symbols, the reinforcement of stereotypes, and the erasure of the cultural context from which these elements originated. It is essential to recognize that the impact of cultural appropriation extends beyond the realm of artistic expression, influencing societal perceptions and perpetuating power imbalances.- CAT - 2025

- Para Summary

- In the set of consecutive odd numbers $\{1, 3, 5, \ldots, 57\}$, there is a number $k$ such that the sum of all the elements less than $k$ is equal to the sum of all the elements greater than $k$. Then, $k$ equals?

- CAT - 2025

- Number Systems

- The number of distinct pairs of integers $(x, y)$ satisfying the inequalities $x>y \ge 3$ and $x + y<14$ is:

- CAT - 2025

- Number Systems

- If $a - 6b + 6c = 4$ and $6a + 3b - 3c = 50$, where $a, b$ and $c$ are real numbers, the value of $2a + 3b - 3c$ is:

- CAT - 2025

- Linear & Quadratic Equations

The given sentence is missing in the paragraph below. Decide where it best fits among the options 1, 2, 3, or 4 indicated in the paragraph.

Sentence: While taste is related to judgment, with thinkers at the time often writing, for example, about “judgments of taste” or using the two terms interchangeably, taste retains a vital link to pleasure, embodiment, and personal specificity that is too often elided in post-Kantian ideas about judgment—a link that Arendt herself was working to restore.

Paragraph: \(\underline{(1)}\) Denneny focused on taste rather than judgment in order to highlight what he believed was a crucial but neglected historical change. \(\underline{(2)}\) Over the course of the seventeenth century and early eighteenth century, across Western Europe, the word taste took on a new extension of meaning, no longer referring specifically to gustatory sensation and the delights of the palate but becoming, for a time, one of the central categories for aesthetic—and ethical—thinking. \(\underline{(3)}\) Tracing the history of taste in Spanish, French, and British aesthetic theory, as Denneny did, also provides a means to recover the compelling and relevant writing of a set of thinkers who have been largely neglected by professional philosophy. \(\underline{(4)}\)

- CAT - 2025

- Para Completion